The American federal budget has been in the news in the last couple of weeks. And there is one thing about it that is, I think, worth noticing. It is worth noticing because it forms part of a larger picture of the way that military policy, and thus foreign policy – and, in particular, Middle East policy – is going under Trump.

What is happening is, in some ways, not a big departure from what happened under Trump’s predecessors, and thus is not attracting much attention or comment. Most Americans don’t seem to be particularly concerned about it.

I think, however, that they should be. And so, for that matter, should non-Americans.

There are six things that have happened in the past year that I think show us what is going on.

Defence spending

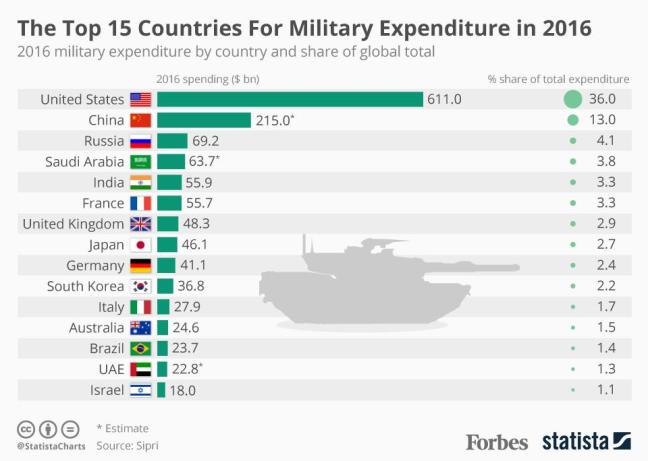

This week, the White House unveiled its 2019 budget proposals. Among its suggestions is defence expenditure of $716, a proposed 13 percent increase on 2017 when the United States spent about $634 billion on defence. Putting this in perspective, this compares with a 3.76% increase in 2017. And, for the record, according to the World Bank, US GDP growth was 2.4% in 2014, 2.6% in 2015, and 1.8% in 2016. The US Defence Budget is already the world’s largest, by a considerable margin – someone recently commented that the US has 5% of the world’s population, but 50% of the world’s military spending.

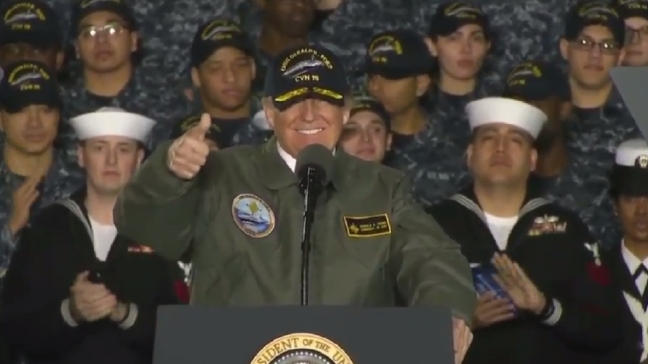

Donald Trump, speaking to reporters on Monday, said:

“One of the other things I think so important to mention is that, in the budget, we took care of the military like it’s never been taken care of before. In fact, General Mattis called me; he goes, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I got everything we wanted.’ I said, that’s right, but we want no excuses. We want you to buy twice, OK?”

Trump’s generals

Along with a commitment to a huge increase in military spending, Donald Trump has got a surprisingly high number of top military men in his administration. Three high-ranking generals are his close aides in the White House: National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster, Secretary of Defence James Mattis and Chief of Staff John Kelly. It all gives the impression that Trump is more enthusiastic than most presidents about the military.

Syria

If Trump’s enthusiasm for military spending and military officers raise eyebrows, they are not nearly so astonishing as the fact that the U.S. recently announced that it will maintain an open-ended military presence in Syria. I’ll repeat Daniel Larison’s comment:,

“To call this policy deranged would be too generous. The U.S. has no business in having a military presence in another country without its government’s permission, and it has no right to maintain that presence for the explicit purpose of preventing that government from exercising control inside its own internationally recognized borders. If another state did what the U.S. is now doing in Syria, Washington would condemn it as an egregious violation of international law and would probably impose sanctions on the government in question.

U.S. forces are in Syria without authorization from Congress and they have no international mandate to be there. A continued U.S. presence in Syria is both illegal and unwarranted.”

Lebanon

And, while we are on the subject of “deranged”, there is the matter of what happened to Lebanon’s prime minister, Saad al-Hariri, in November. The Saudi government asked him to come to Saudi Arabia. When he arrived, the Saudi government basically seized him, and ordered him to go on Television and resign. They then proceeded to hold him for several days, until, apparently under pressure from France, they allowed him to leave. He returned to Lebanon, where he withdrew his resignation.

Saudi Arabia’s behaviour was not just unacceptable, but totally bizarre. It drew pretty well no public condemnation or serious criticism from any western governments.

What is significant is that not only is America a very close ally of Saudi Arabia, but Trump himself has a good relationship with the Saudi leadership, and has spoken very positively about them.

Afghanistan

After all that, Trump’s Afghanistan strategy, as announced last August, seems pretty uncontroversial.

In his speech, he said his original instinct was to pull US forces out, but had instead decided to stay and “fight to win” to avoid the mistakes made in Iraq. He said he wanted to shift from a time-based approach in Afghanistan to one based on conditions on the ground, adding he would not set deadlines.

But if that sounds uncontroversial, it is laughably unrealistic to think that America can “win” in any meaningful sense in Afghanistan. The policy is about as deranged as the Syria policy or the Saudi attempt to get Hariri to resign.

Trump’s Parade

As noted, Trump seems to have an enthusiasm for things military. And so last week, it was not a huge surprise when it emerged that he had asked the Pentagon to organise a large military parade in Washington DC. He made the request of top military chiefs in late January, after reportedly being impressed by a French Bastille Day parade last year. “It was one of the greatest parades I’ve ever seen,” he later said. “We’re going to have to try and top it.”

Nonetheless, it is unusual. Military parades in Washington are usually only used to mark victory at the end of a war.

And the significance of all this?

Andrew Bacevich, Professor Emeritus of International Relations and History at Boston University, and a former Colonel in the US Army was asked to comment on the proposal for the parade-without-a-victory. His remarks are well worth thinking about.

“in a weirdly ironic way, perhaps Trump’s proposed parade-without-a-victory captures something important about the present moment in American history. In former times, we organized parades to celebrate wars won. There was a common understanding that the intended outcome of war was victory. Or to put it another way: the purpose of war was to achieve the political objectives that provided the basis for the war. War was to be, as Clausewitz wrote, the continuation of politics by other means.

In the endless wars since 9/11, we have lost sight of that principle. Our wars have become purposeless, a fact that American elites and the American people appear to find acceptable. Having a parade to honor a military that does not win and that the country has consigned to endless campaigning in distant theaters seems somehow oddly appropriate.”